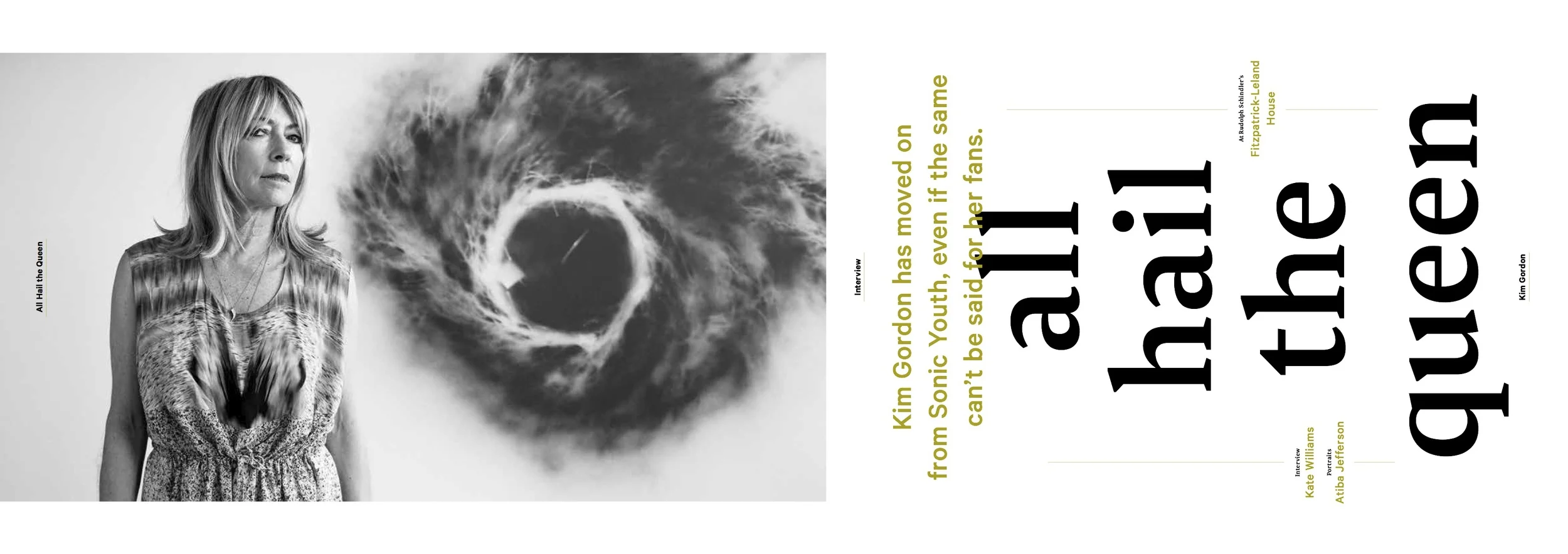

All Hail The Queen

Kim Gordon has moved on from Sonic Youth even if the same can’t be said for her fans.

Kim Gordon is a classy lady. In 2011, when news broke of her split from husband and Sonic Youth bandmate Thurston Moore—to whom she’d been married for 27 years—Gordon was mum. Not so everyone else.

Fans behaved like a 13-year-old who had just been told that dad was getting his own apartment. “So.... yeah. I no longer believe in true love,” wrote Amy Phillips in Pitchfork. Grantland called it an “Unkool Thing,” then wailed “Whyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy” with exactly that many ys. Spin, clearly trying to remain calm and mature about the situation, called it “the final nail in the ‘90s alternative rock dream.”

More than two years later in an interview with Elle magazine, Gordon revealed the reason, or at least part of it, why she and Moore had split: He cheated. Once again, the internet burst into tears. When Moore confirmed the affair in an interview, yet another year after that, it once again made headlines. The website Jezebel called Moore “a dickhole,” and Moore in turn called them gender fascists.

Still following here? Ok, good, because this interview with Kim Gordon happened just a couple of weeks after that. Gagosian Gallery was presenting an exhibition called “Coming Soon,” a series of 24 paintings that Gordon did working as Design Office. The exhibition took place at Rudolf Schindler’s Fitzpatrick-Leland House, a starkly beautiful minimalist home in the Laurel Canyon hills above Los Angeles. I arrive early for the interview, and in chatting with the director overseeing the show, I mistakenly say the two words he, as a gallerist arranging interviews about Kim Gordon’s paintings, probably doesn’t want to hear: Sonic Youth. That, he politely but firmly tells me, is not what this interview is about.

I smile and nod. Of course it isn’t. Mentally, I rip out the page of my notebook where I have written all of the questions about Sonic Youth.

Gordon arrives at the house on time, and crunches into the gravel driveway in a car that is so indistinct it must be a rental. She is also a fashion icon—so much so that Hedi Slimane shot her as a face of his first Saint Laurent campaign—and the outfit she is wearing today does not disappoint. White dress, white LD Tuttle shoes that she got at Creatures of Comfort in Los Angeles, and gold jewelry—the kind of sublimely simple clothes worn by someone who has spent a lifetime just looking fucking great.

Kim Gordon is so cool that people feel compelled to leave comments on her Instagram such as “I hope you never fucking die because you’re a fucking legendary badass bitch,” [actual quote], but in person, she’s warm and friendly. She jokes with the gallery staff as they make coffee and rehash the past weekend’s opening. She even compliments my shoes.

Outside, she and I sit down in butterfly chairs on the porch. It’s a typical day in Los Angeles, beautiful and perfect. Birds chirping. Wind in the trees. After Gordon and I settle in, the gallerist steps outside and asks if we mind if he smokes. Not at all! Smoke away. It’s a large yard, with multiple levels, several seating areas and a driveway out front, but he sits down a few feet away from us. He stays for the entire interview.

So, be prepared—this interview won’t be answering what everyone who grew up listening to Daydream Nation and Goo really wants to know: What’s going to happen to our favorite band? But while it would be impossible to talk about Sonic Youth without talking about Kim Gordon, it actually is possible to talk about Kim Gordon—or, at least, to her—without talking about Sonic Youth. Though it may be her most well-known and culturally successful venture, 30 years as the bassist of one of the most seminal rock bands of all time is only one act in an oeuvre that includes acting, fashion design, writing, and, perhaps most of all, art.

Her latest undertaking is a series of 24 paintings that she made on site, working in the basement of the same house where the paintings are now hung through out the rooms and, in one case, balanced on a bed. It’s a show that is in part an investigation of how art lives in the real world, outside of a gallery. “I’ve been watching a lot of home shows lately, and on these real estate shows, they’re always talking about ‘staging the house,” she says, “My first idea for this show was to do it in a model home, because I’m always really interested in how they use art in those homes, and the names of the housing developments. I used to go around and look at those developments with a friend of mine who studied architecture, and it always stuck in my mind that I wanted to do a show there.” The Schindler Fitzpatrick-Leland house, while far from a suburban subdivision, was in fact the kind of house that she was looking for, as it was commissioned by a real estate developer to lure buyers up onto the hill. “So it is a tract house, just a super nice one!” Gordon laughs. “And there is something about this location and the architecture that has a sense of drama. It’s like something just happened, or something’s about to happen, with the sense of shadows and the voyeuristic aspects of the windows.”

The paintings inside are wreath paintings, made from acrylic paint in blue and metallic shades, and wreaths that she picked up in a craft store. There are also a few carefully selected props staged around the house, like pairs of tights flung on the floor (a familiar Instagram theme for Gordon) and a Joan Didion book. “I really love her writing, and the way she writes about L.A.,” Gordon says. “I had this text I had written about growing up here and Laurel Canyon versus the boring flatlands, and it was supposed to be a personal tour of Los Angeles. I hadn’t actually read any of her at that time, but then someone said ‘Your work is like Joan Didion.’ Some writers sound so female, and hers doesn’t, and hers doesn’t in way I relate to in my sensibility with music.”

Her cell phone, balanced on her knee, has been dinging with texts through out the interview. It dings again, and this time she picks it up. “Here’s that photo,” she says, leaning over to show me a picture from the show’s opening night, the house’s aquarium-like windows glowing blue and people standing around on the lawn like they were at a barbecue.

This show is under the name Design Office, a moniker that Gordon created in the early ‘80s and has recently started using again. “Design Office was just something that sounded like it was collaborative,” she explains. “Vikky Alexander and I started it, though she didn’t really end up doing anything with it, mainly as just an excuse to hang out. We were both outsiders to New York, so this was a way for us to feel like we had a group.” She laughs. “A faux group. Then I had the show at White Columns [in 2013], I decided to go back to using that word, and in a sense to put everything I do under the umbrella of Design Office. It immediately connects everything, and makes it more like my life a more conscious involvement in popular culture.”

As she’s moved through her career, Gordon has become a pop culture icon while still managing to comment on it and participate in it. She has designed clothing collections for Urban Outfitters, appeared on a season premiere of Girls, painted Lena Dunham’s tweets and made works that were giant, dripping letters spelling out things like ‘Bad Adult,’ ‘Afternoon Penis,’ and ‘Hair Police.’ She tackles her own place in pop culture with a sense of both professionalism and amusement. During our interview, when she mentions someone by name she will then spell it out before being asked, always aware of the fact that her words will go on to be transcribed and fact checked. But she also notes that one of her dream projects would be to have someone document every fashion magazine shoot she’s asked to do. “Pop culture is our modern landscape,” she says with a sense of a shrug. “Twitter is totally like a landscape. Europe has history. That’s their landscape, and this is ours.”

One of the most amazing things about Gordon’s career is that she has managed to maintain a vibrant art practice even when Sonic Youth was a full-time job of sorts. “When I was in the band, it was hard to maintain a career in art, but I did try to keep my toe in it, and started to do installations and shows. I always wanted to do all of these things. I was always torn between art and dance, and then when I started playing music, it was a really visceral thing for me,” she says. “I’m really sort of focusing more on visual art now, it’s just hard to balance.”

In the 1990, Gordon also had a band called Free Kitten with Pussy Galore’s Julia Cafritz, and currently she has a duo called Body/Head with her friend Bill Nace. “I didn’t think I was going to do more music,” she admits, “but I like playing with him.” The idea that she could not play music anymore might surprise some of her fans, but Gordon was an artist first. “I’ve long tried to keep the art separate from the music, and I’m often asked to be in shows with musicians that do art, but I usually avoid that because I feel like unless I have some relationship to their artwork or their music.”

“I know, it sounds ridiculous. But I’ve always worried, especially in the art world, about being considered a dilettante,” she admits. “But some of the best artists were considered dilettantes, like Yves Klien was so eccentric. And But some of the best artists were considered dilettantes, like Yves Klein was so eccentric. And I’ve long tried to keep the art separate from the music, and I’m often asked to be in shows with musicians that do art, but I usually avoid that because I feel like unless I have some relationship to their artwork or their music, it doesn’t make any sense.”

However, Gordon is currently also working on a memoir, which is tentatively titled “Girl in a Band.” It’s tongue in cheek and deliberately diminutive, a nod to how other people saw her even if that was never how she saw herself. “When we first started going to England, everyone would be like, ‘What’s it like to be a girl in a band?’ and that’s like the stupidest question every female musician hears,” she laughs. “But it made me start thinking, and I became suddenly very self conscious about it. People have weird ideas about projecting stuff on you. Like, oh, ‘You’re a strong woman, thusly you must be photographed in the harshest way. It’s sort of a reverse sexism.”

Gordon adjusts her skirt, and it hits me how much pressure it must be being the world’s coolest woman. “I don’t feel like a strong woman, and I don’t even really know what the idea of a strong woman is,” she continues. “No one ever really talks about what that means. I think you have to really make yourself look vulnerable to be effective in whatever you’re doing, whether you’re a man or a woman, and be kind of a fearless risk taker in your work. It’s not like you feel confident. It’s kind of like jumping off a cliff.”

I ask her if, 30 years into an insanely successful career, she still feels like that. “Sure,” she smiles. “Just maybe not as high. A small cliff.”